Photos: Pavel Acosta

Lehman College Art Gallery | City University of New York

February 4 – May 14, 2014

Reception: March 17th, 2014, 6:00 – 8:00 pm

(The reception will include a special performance by artist Carmelita Tropicana.)

This project is co-curated by Yuneikys Villalonga and Susan Hoeltzel

Alejandro Aguilera | Jairo Alfonso | Alexandre Arrechea | Tania Bruguera | María Magdalena Campos Pons | Yoán Capote | Los Carpinteros | Luis Cruz Azaceta | Christian Curiel | Alessandra Expósito | Teresita Fernández | Carlos Garaicoa | Anthony Goicolea | María Elena González | Armando Guiller | Luis Mallo | María Martínez Cañas | Abelardo Morell | Gean Moreno & Ernesto Oroza | Glexis Novoa | Geandy Pavón | Emilio Pérez | Javier Piñón | Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas | Andrés Serrano | Katarina Wong

Video program: Juan Carlos Alom | Allora and Calzadilla | Humberto Díaz | Felipe Dulzaides | Luis Gárciga | Tony Labat | Glenda León | Ana Olema

The video section is curated by guest curator Meykén Barreto

See Checklist in Lehman College Art Gallery’s Website

Cuban America: An Empire State of Mind includes over 35 contemporary artists of Cuban descent, who have been raised and/or educated in the States or in Cuba. In this exhibition, a myriad of themes are inspired by America: as the familiar homeland for second and third generation children of Cuban parents, or as the distant, imagined place, that has historically empowered diverse ideologies on the Island. These views, rarely put together, portray multiple landscapes of the concept of empire, so easily associated with both countries. They add many nuances to the complexity of the cultural relationships between Cuba and America, often simplified to politics.

El Che y Carlos Santana, 2006, by Alejandro Aguilera is a sculpture made from recycled pieces of wood, Georgia clay, metal, and graphite, among other materials connected to the tradition of popular wooden sculpture in the American South. A standing, disproportioned figure with stylized head and long hair crowned with a halo, resembles a wooden saint. Instead, here the controversial hero and the rock star intersect, and with them their ideologies, ideals and nature. The piece recalls the moment when Santana appeared wearing a Che T-shirt at an Academy Awards Ceremony – an action that unleashed a furor of protests in the States because of the infamous reputation of Guevara as a ruthless man. Other historical characters are drawn on the flat back of the sculpture, among a wooden structure of shelves, turning it into a kind of shrine.

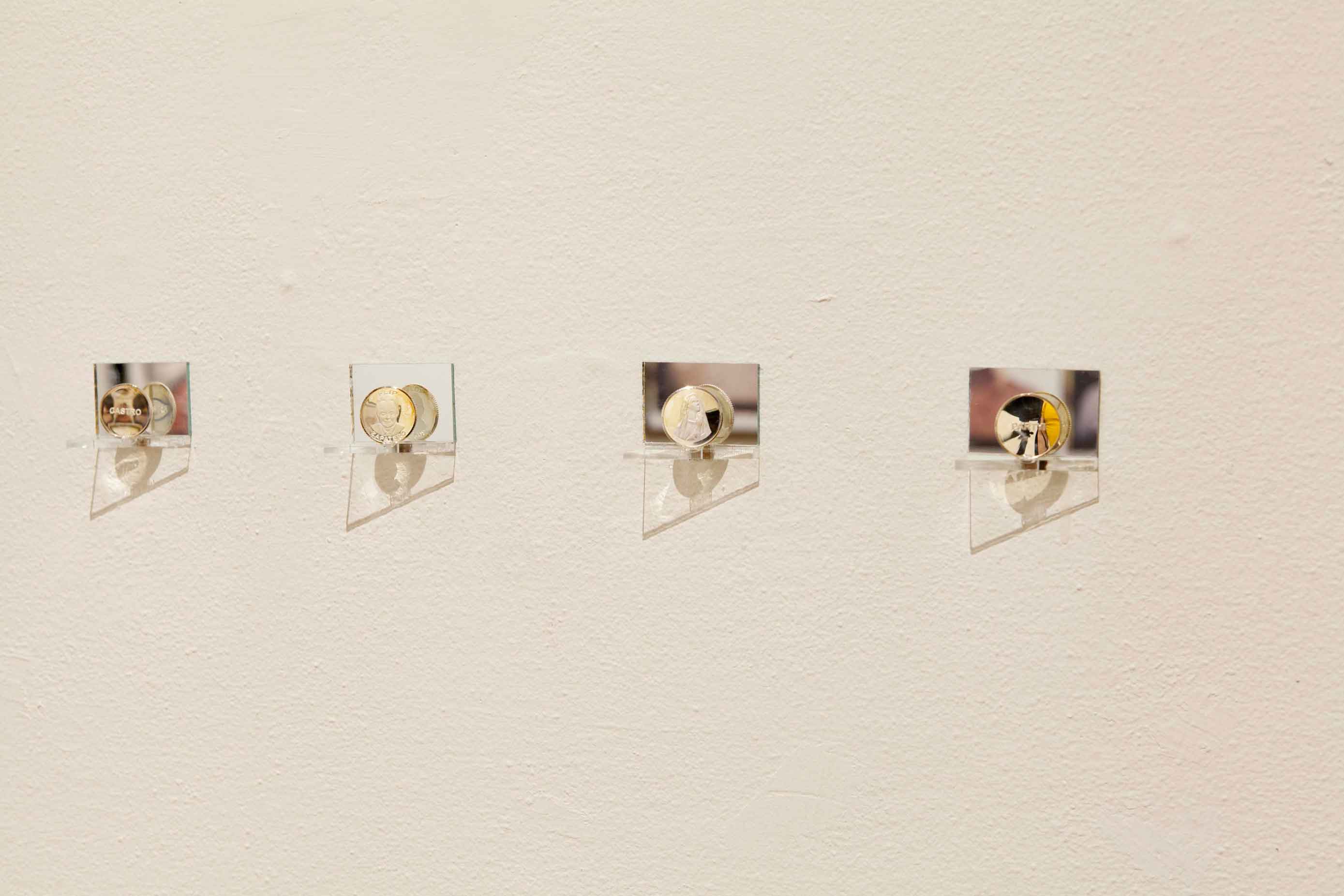

Carlos Garaicoa’s four silver coins, from the series Heads or Tails, 2010, also introduce a reflection on the dual nature of images and texts. They make reference to political issues, which appear as opposing forces or complements, only for us to discover that they are literally “sides of the same coin.” Flip/Flop bears the surnames of Mariano Rajoy and José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, Spanish political leaders of the right and the left wings, respectively; Fundamentalisms depicts a Catholic woman versus a Muslim woman, while the other two coins share the texts in their titles: Party/Not Tea Party, as a reference to the conservative American political movement; and Castro/Castro, that relates to Cuban leaders.

Tatlin’s Whisper No. 6, 2009, by Tania Bruguera, takes advantage of a structure that has been used in Cuba to protest against the US government for the last 50 years to address freedom of expression in Cuba. On view is the video documentation of her performance of the same title that took place during the X Havana Biennial of Contemporary Art. Bruguera built a stage similar to that used by politicians in Cuba to make speeches. After distributing disposable cameras within the audience, she invited the public to stand on the podium and talk freely for a minute, after which they would be conducted out of the tribune by a couple dressed in military outfits. During the time people spoke, the couple would place a white dove on the shoulder of the speaker. This action created a reenactment of what happened during Fidel Castro’s first speech in Havana, in 1959, when a white dove landed on his shoulder and was interpreted as a religious omen.

Another piece addressing freedom of expression on the Island is the edition No. 29 of The Tabloid, 2014, an editorial initiative of artists Ernesto Oroza and Gean Moreno. For this issue, launched here at Lehman College Art Gallery, Oroza and Moreno invited artists Ana Olema and Annelys PM Cassanova to provide the design and content. The outer page of the tabloid bears a wallpaper design, used in the exhibition to cover the central column between the galleries, where the public can pick up a copy to take home. Its design is the drawing of “Zamora’s Rainbow Brush”, a digital tool for Photoshop and Illustrator Ana Olema and Cassanova are launching. It reproduces the patterns on the facade of the home of one of the members of the opposition in Cuba – Lisset Zamora – after a group of people threw asphalt at her house, in punishment for her opposition. This edition uses asphalt as the central subject from which multiple associations can be made.

Visual/verbal mixed metaphors and “plays on words” characterize many of the works of Yoán Capote. His “I Want You for the War“, 2004, is a riff on the familiar Uncle Sam poster. A long steel cylinder with a bronze forefinger at one end, is accompanied by the inscription “I want you.” At the other end of the cylinder, the text “for the war” is positioned next to a rifle site. In a second work in the exhibition, In tran/sit, 2003, a few suitcases form an impromptu bench on which a lone figure sits. It captures the tedium of both travelers and immigrants when having to deal with “a heavy load.” The drawing is a study for a cast concrete and stainless steel sculpture of a bench.

Luis Cruz Azaceta’s allegorical landscape, Shifting States: Iran, 2011, is encoded with symbols of power, conflict, and change on the horizon. Technology fuels each arena as the past and the present merge with cell phone towers, satellite dishes, mosques, and churches, forming the architecture of cities. The imagery offers a frenetic rush of lines and shapes with the dimensional texture of paint, symmetrically divided about and below a central horizon line. In this dystopian vision, Azaceta finds hope for the future in the recent shifts in the Middle East, also enhanced by technology.

On the other hand, Private Drone, 2011, a mixed-media-on-paper work by Glexis Novoa, proposes a differing vision of a futuristic landscape. A colossal drone occupies the center of the composition against golden striped clouds, while other smaller planes fly in the distance. The horizon line, traced with a thin wire that juts out of the sides of the paper, is the bottom line for tiny drawings of a communications tower in Miami, a Russian bust of Lenin, Havana’s National Hotel, and other symbolic elements and architecture from different cities of the world.

Landscape is a subliminal presence in Emilio Perez’s a mighty good reason, 2010. Its gestural abstraction resonates with the sweep of ocean currents and crashing waves – as if feeling as well as seeing the ocean. (He has been a surfer for many years.) The works begin with layers of paint over a wooden panel, first latex, then acrylic, into which Perez cuts and removes strips of acrylic. His lines take shape intuitively, viscerally. Perez collects phrases that he comes across while reading and often uses them as titles for his paintings.

Teresita Fernández’s panoramic Night Writing (Tropic of Cancer), 2011, depicts the aurora borealis. Created using hand-made paper pulp backed with mirrors, it is a unique photographic print that shimmers like the night sky. “Night writing” alludes to a code developed under Napoleon, intended to convey information without light or sound. It became the basis of braille. In this series of works, indecipherable words in the form of braille-like perforations struggle to communicate language. The Tropic of Cancer, a latitude marking the northern most path of the sun, falls between Cuba and the US.

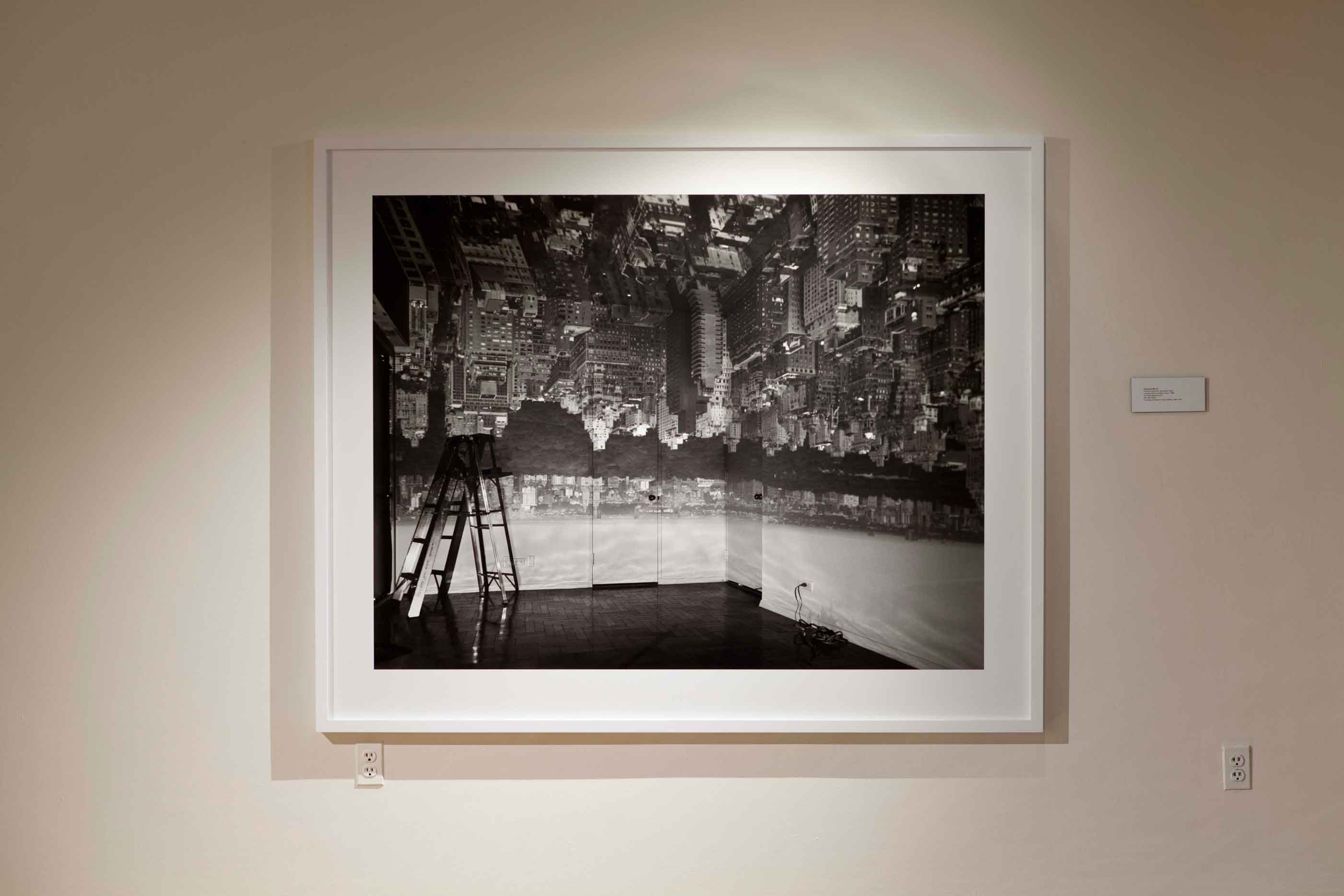

Along with natural and imaginary places, cities and their architecture have been an inspiration for many of the artists in the exhibition. Transforming a room into a pinhole camera and photographing the results, Abelardo Morell creates disorienting views of familiar surroundings using one of the oldest techniques for creating a photographic image. In Camera Obscura: Manhattan View Looking West in Empty Room, 1996, he superimposes an inverted, exterior view on an interior wall. An empty apartment with only a ladder, perhaps being prepared for the next tenant, is overlaid with a panoramic view of New York City’s Upper East Side, West Side, and Central Park, which fills its walls and ceiling.

In The Key of New York City, ca. 1998, a painting by Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas, the skyline of Manhattan is superimposed over a sword. After having lived in NYC, the artist moved across the Hudson River to an apartment with a view of Manhattan: a landscape that triggered many associations regarding placement and identity. The city as a key, as an island, or a ship connects both his homelands – Cuba and New York. Imagery is reduced to simple geometric forms. The transparency of the pastel colors allows certain depth, as buildings overlap each other, while disappearing in the distance, as if the city was buried in the fog.

Geandy Pavón’s Empire, 2013, is part of a body of work in which the artist depicts wrinkled photographs or pieces of paper with iconic, often historical and political images. A trompe l’oeil paper lays against and casts shadows into an otherwise empty canvas. A photograph with a panoramic view of Manhattan’s skyline looks as if it had been crumbled before. A pearl necklace curls up on top of it and picks up the golden light of the picture. In the shift from being a photograph to becoming a still life, the represented image carries Pavon’s own relationship with its content.

Empire State, 2012-2013, and Chrysler, 2013, from the series No Limits by Alexandre Arrechea, are maquettes for the larger pieces installed last year along New York City’s Park Avenue. While the façade and main attributes of the Empire State and the Chrysler buildings are still recognizable in the works, they are modeled into other objects and architecture – the Pentagon, in the case of Empire and a hose-snake, for Chrysler. Making use of the concept of “elastic architecture,” these landmarks are morphed after economic, political, and social changes in their surroundings.

With a background that combines visual arts and mechanical engineering, Armando Guiller applies math formulas to conceive sculptures such as Helical Work 4, 2006, where the helix is a leitmotif to arrive to its final appearance. In this work, precisely cut sheets of steel and birch plywood of identical shape are combined and lay on top of each other, around a central bar. Slightly spinning in one direction on their way up, these pieces form a spiral column. Studies of rhythm and sound, as well as architecture – especially that of New York – have also influenced Guiller’s work.

In Camera No. 19, 2002, by Luis Mallo is part of a wider series where different landscapes can only be seen through fences of all sorts. In this work, a dark green net fence obscures the view of a wild green area near a red house. Lively colors can be discovered through a small opening in the net, from which we can imagine the rest of the picture.

María Martínez Cañas’ Untitled [Eakins], 2007, was born out of the photographs taken by José Gómez-Sicre, a prominent mid-century Cuban curator, and friend of the family, who was among the first to promote Latin American art in the United States. His archive includes images from his travels to exhibitions throughout the Americas. After choosing some of these photographs, Martínez-Cañas lays a sheet of tracing paper over part of the images, highlighting some of the lines and shapes, to recreate the compositions. Together with the rest of the works from her Adaptation and Tracing series, they become the artist’s personal curatorships with which to provide crossed references and comments that range from the personal to the art historical.

María Elena González’s Climb II, 2007, is a triangular sculpture made of a frosted plexi that encases an inner wooden triangle. Stairs form one side of the wooden structure and although they can be seen, the steps cannot be climbed. This work was inspired by González’s experience in Rome, where she became fascinated with Catholic reliquaries, and frustrated with not having access to the relics inside of them. This sentiment of alienation transcends that context into other personal and social realms.

Identity and the body have been dominant themes in María Magdalena Campos-Pons’ work, along with memory and the experience of displacement. In When I am not Here/Estoy allá (Identity), 1998, three photographs depict the artist covered in brown and white makeup with Spanish and English texts – “here,” “allá”(there), “identity could be a tragedy,” and “patria una trampa” (homeland is an entrapment). African culture also plays a role in this series of large format Polaroid prints – with particular references to the syncretic practice of Santeria and to the orisha Elegguá, who opens pathways. His hooked stick, the garabato, is seen in one of the three photographs and his colors, red and black, dominate many of the works in this series.

Anthony Goicolea, a first generation Cuban-American, uses his family lineage as an avenue to explore the sense of cultural dislocation, which often accompanies immigration. Aunt (Positive Negative Diptych), 2008, part of his on-going series, “Related,” depicts a likeness of a family daguerreotype by drawing in negative an image of his aunt as a young girl, posed formally in beautiful clothing. This painstaking image reversal process is followed by a photograph of the image which produces a second generation of this portrait, the mirror positive.

Christian Curiel, introduces self-referential elements in Saved, 2013, an oil and mixed media on panel work depicting a young man. He wears a black hat and gloves, and a red, short-sleeved top. His facial features are not distinguishable and blend into the background. As in most of his paintings where each character is somehow the artist himself, this work becomes a psychological portrait.

Tarnished Chimp (Monkey Mind), 2013, by Katarina Wong, on the other hand, focuses on an emotional state and is one in a series of animal heads the artist casts and then, individualizes. “Monkey mind,” a term borrowed from Buddhist meditation, refers to the scattered thoughts and chattering in one’s head, in contrast to disciplined focus. The chimp’s bared teeth suggest insight into the animal nature of the creature. A high gloss, glazed surface freezes the moment. Wong’s work acknowledges both raw emotions and the desire for equanimity.

Visual metaphors are employed to probe the psychological in Javier Piñón’s series of collages featuring the all-American cowboy as an archetype and hero. Untitled, 2006, features the protagonist climbing a precariously stacked tower of chairs, capturing a sense of disequilibrium and potential loss of control. Piñón’s sources for these seamlessly combined collage constructions range from vintage rodeo to classic Hollywood magazines, perhaps connected to his childhood in Texas.

Andrés Serrano’sphotograph Wunmi Fadipe, Sales Assistant at Investment Bank, 2002, is from the ”America” series. Created after September 11th, the series explores the diversity of this country through portraiture in an attempt to understand who Americans are. Initially inspired by a request from the New York Times Magazine for photographs for a commemorative issue produced ten days after the attack, the series expanded to over one hundred images of people from many different backgrounds – a Boy Scout, a firefighter, a Playboy Bunny, a homeless man, a postal worker, Snoop Dogg, and Arthur Miller. Wunmi Fadipe’s portrait, 50-by-60-inches, is both monumental and heroic.

Alessandra Exposito’s Cinnamon, 2008, weaves together layers of associations and references. Using an actual horse skull painted pink and embellished with a large rack of antlers from which carrots and a horseshoe hang and flowers are placed, Exposito establishes a fictional narrative around the life of Cinnamon. With his name in script above his portrait, painted on the skull, Cinnamon is also surrounded by painted flowers and snapshots of a human family. At once tied to trophy culture, it also easily qualifies as an adolescent girl’s object of desire. The sculpture too serves as a memento mori.

Jairo Alfonso draws an accumulation of objects from every day life. In 386, 2013, a Remington typewriter, a Singer sewing machine, an American toy car from the 50s, and a piggy bank, are among the many objects drawn closely together and superimposed in a kind of horror vacui. The number 386, in the title, indicates the number of objects drawn. Each of them is life size. This series is inspired by the peculiar behavior of hoarding. Alfonso pairs it with the impulse of consuming. He is interested in how specific objects define a generation, a civilization. At the same time, drawing frantically and cataloguing objects becomes his obsession.

The improbable combination of ordinary objects is the territory mined by Los Carpinteros, a conceptual art collective. (The duo is comprised of Marco Antonio Castillo Valdés and Dagoberto Rodríguez Sánchez, and originally included Alexandre Arrechea, who launched a solo career in 2003.) Trash-Shopping Cart, 2008, a combination trash container and shopping cart, is at once contradictory and an ingenious idea. The artifact itself is a summary of the cyclic process that goes from buying goods to discarding them. With the look of a functional object that is flawlessly mass-produced, it offers humorous comments on consumerism.

Cuban America: An Empire State of Mind brings together a group of artists with diverse impressions of the world they live in today. Some artists reflect on the shifting politics and society in the United States; others envision futuristic landscapes, or reconsider the natural ones through their own, personal experiences. The city and its architecture are common ground for many works, while self-representation and identity find their way through portraits and objects. Works in this exhibition add to the construction of a fresh, as well as complex, image of America: a Cuban America.

Yuneikys Villalonga and Susan Hoeltzel